Good And Bad Scientific Figures

- Surreal in its beauty, a plume of white smoke ushered in the end of America's romance.

- Gay canvassers change minds. The highest-profile retraction of 2015 comes from the journal.

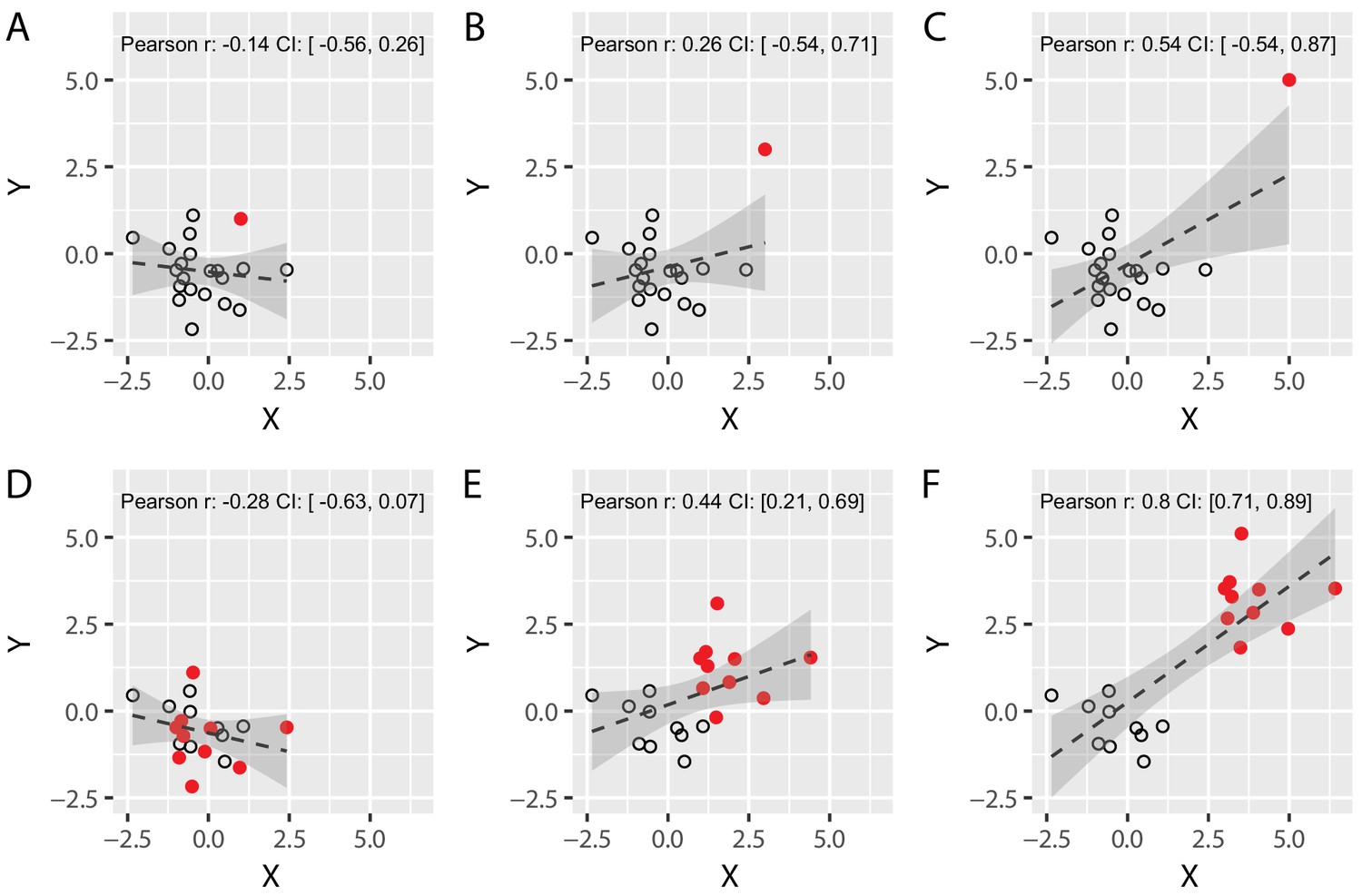

I gave a short introduction to how to give a presentation today to the students who will be presenting their research in our twice-weekly Summer Student Seminar Series. This included examples of a data slide that is bad in the ways that students' first attempts at data slides tend to be bad, and the same graph re-done in a more appropriate manner. As long as I'm doing format conversions of this anyway, I figure it might be amusing to post them here. So, here's the bad graph, with the bullet points highlighting the mistakes:

And here's the good version:

(The seminar series features three talks per session, at twenty minutes per talk (15 minutes plus 5 minutes for questions), usually with a short break between speakers when students can re-load on food and drink.)

Number of figures allowed in a paper and by eliminating color costs. Within the last several years, PubMed and journal websites have begun to display thumbnails of figures alongside abstracts for all of their indexed publications. This means that from the initial search for your paper, your figures are already making an impression.

Edward Tufte, I'm not, but I think these help to make the important points. Of course, I'm probably forgetting lots of things that really ought to be mentioned regarding presentation slides. Feel free to remind me of them in comments.

- Log in to post comments

Writing a scientific paper? Preparing for publication? Making a poster for a conference tomorrow? Let’s face it: People will skim through the body text of your paper/poster, and only look at the figures. We all love figures. They catch eyes, they deliver information effectively, they highlight your results. Figures are the star of your paper. Your job is to make them shine.

We’ve talked about good and bad charts before. After making a good chart (or a figure of any kind), you will have to describe it. That’s what the legend (a.k.a caption) is for. A good legend will make or break a graphic. This post will give you a few tips to write and format figure legends for scientific papers.

A figure should be able to stand alone. Readers want to understand it without going back and forth between the figure and the text sections. Don’t tell your readers to “See Methods” — most of them won’t look through the maze of text to search for the exact spot where you buried this piece of information.

How to write a good legend that makes a figure clear as day, all by itself, in a scientific paper?

1.The title:

The title should tell the readers “This is what this figure is about” very clearly. Use active voice, and keep it short.

Make it a sentence that summarize the major result seen in the figure.

Example: Hippocampal neurons derived from patients with bipolar disorder show hyperexcitability.

Or, make it a phrase stating the type of analysis used.

Example: Quantification of XYZ transgene expression using RT-PCR.

2.The methods:

This is where things tend to get out of hand. It is true that you should include lots of details, like assay name, antibodies used, cell type or animal model, treatments and controls, statistical tests, numbers of replicates, et cetera. The figure must be able to stand alone. You want your readers to understand it without going back to the method section.

Good And Bad Scientific Figures Crossword Puzzle

But on the other hand, you don’t have to rewrite the method section. Limit what to include in the legend to the absolute minimum that is required to understand the figure.

Example: Average expression of representative genes involved in the PKA/PKC and AP firing systems revealed by RNA-seq (a) and qRT–PCR (b) analysis (normal, n=4; BD, n=6 lines).

3. The results:

You really only need this if i) the title did not state it already, or ii) the figure has multiple panels or shows multiple results. Either way, contain the temptation to go on and on about your findings, and keep this part short and sweet. Limit it to one or a few sentences that describe the key findings that are seen in the figure.

Example: Patch-clamp recording on Prox1::eGFP-expressing neurons showed spontaneous postsynaptic currents.

Side note: You might not have a choice to keep the legends short. If you are publishing with Science or Nature (congratulations!), they put a limit on body text, so a big chunk of the Methods and Results sections ends up in figure legends, hence their “signature” super long legends. A rule of thumb: Always follow the journal’s specific instructions.

Making your figure legends look good doesn’t just satisfy your inner artist. An attractive, professional looking legend grabs attention. Here’s a few keys to get “the look.”

1. Avoid clutters:

When possible, place all labels on the graphics. That will make it easier to read both the graphs and the legends.

Tone down on abbreviations. If you must use them, make sure they are consistent with the text of the paper, and that they are common acronyms and not the obscure system that only your lab uses to manage the tubes.

2. Pick a good font

Examples Of Good And Bad Scientific Figures

The debate over the best font for a graph legend in scientific papers has not come to an end. Meanwhile, here’s the consensus so far:

- Follow the journal’s instructions (duh!)

- If there is no instruction, use the same font as the body text, and run it one size smaller.

- DO NOT TYPE ALL CAPS!

Good And Bad Scientific Figures Definition

Still overwhelmed by options? Pick one from the “People’s Choice” fonts: Arial, Helvetica, Computer Modern, or Times New Roman.

3. Sizing and margins:

Legends should match the width of the figures. Place them above a table, but below a figure (charts, graphs, images, etc).

What Is Scientific Figures

Legends should be left justified. And don’t forget the period after Figure x. Not comma, not colon. A period.

An effective legend is the key to help a figure stand alone. The title should describe what the figure is about. The methods include all (and no more than) the necessary details to understand the figure without referring back to the body text. The results show the key findings as seen in the figure. Keep everything as short as possible. Avoid clutters, pick a good font, and position it right. Keep the legends consistent with the body text of the paper. And most importantly: make sure to follow the journal’s instructions.

Good And Bad Scientific Figures Worksheet

*Jerome Mertens, Qiu-Wen Wang, Yongsung Kim, Diana X. Yu, Son Pham, Bo Yang, Yi Zheng, Kenneth E. Diffenderfer, Jian Zhang, Sheila Soltani, Tameji Eames, Simon T. Schafer, Leah Boyer, Maria C. Marchetto, John I. Nurnberger, Joseph R. Calabrese, Ketil J. Ødegaard, Michael J. McCarthy, Peter P. Zandi, Martin Alba, Caroline M. Nievergelt, Shuangli Mi, Kristen J. Brennand, John R. Kelsoe, Fred H. Gage, Jun Yao. Differential responses to lithium in hyperexcitable neurons from patients with bipolar disorder. Nature, 2015; DOI: 10.1038/nature15526